After 27 years working as an econometrician I have learned that models often reveal more about the assumptions of the builder than about reality itself. We simplify, abstract, adopt a linear approach and hope that the residuals don't betray us. Yet time and again we see that the real difference between success or failure often lies outside the model. And one factor keeps recurring: leadership.

This is not just an observation. It is a methodologoical problem. Econometric models excel at capturing structural relationships between measurable variables: capital, labour, productivity, interest rates. But the decisions that drive those flows are made by individuals, and individual behaviour proves stubbornly difficult to model.

The problem of unmeasured variables

In classical econometrics we know the problem of omitted variables. If you fail to measure a crucial factor, you obtain biased estimates of the factors you do measure. Leadership seems precisely such an omitted variable. Two companies with identical financial metrics can follow completely different trajectories, depending on how their management handles uncertainty, innovation and team dynamics.

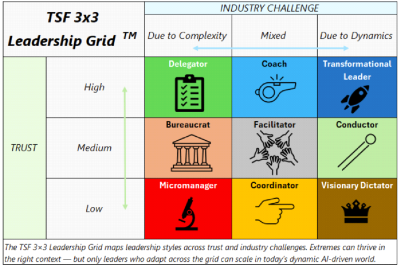

The Trust Solution Framework (TSF) is my attempt to open this 'black box'. It brings together two observable dimensions: the level of trust within an organisation and the dominant challenge that organisation struggles with, complexity or dynamism. From this emerges a 3x3 matrix identifying nine leadership styles.

Based on my practical experience as well as numerous scientific studies, the level of trust within organisations is one of the most important drivers of success. However, without the context in terms of degree of complexity and/or dynamism the relavance of trust is limited. Complex sectors such as nuclear energy (on the left) require different skills than dynamic sectors such as tech (on the right). In other words: a skilled bureaucrat as manager of a nuclear reactor may be a better idea than a transformational leader.

The core idea: different situations require different leadership styles. But whereas much leadership literature is normative ("be transformational"), TSF attempts to be descriptive. A key insight is that the best solution for the short term is not necessarily the best for the long term. Over the long run the management styles on the right side of the matrix have a clear advantage: higher dynamism requires more adaptive leadership.

The Apple case: a natural experiment

Apple Inc. under Steve Jobs and Tim Cook offers a rare natural experiment. Jobs operated as a "visionary dictator": brilliant at innovation, but with low tolerance for dissent. Cook shifted to much higher trust and delegated decision-making. The interesting part is why the timing aligned. Jobs' dictatorial style fit Apple's innovation phase; Cook's delegating style fit the scalling and ecosystem phase.

Moreover, under Jobs the leadership style varied per division, dictatorial in design, more facilitative in manufacturing and sales. The success of perhaps the most successful company of the past 20 years was thus partly based on perfect alignment between leadership styles and needs.

Empirical findings

Specifically I analysed stock returns of 'delegator-investments' (ASML Holding N.V., Nestlé S.A., Swedish and Swiss indices) versus 'dictator-investments' (Tesla Inc., Chinese state-owned companies, oil majors) over 5- and 20-year periods. The results show consistently higher risk-adjusted returns for delegator systems, especially over longer time horizons. These patterns remain robust even after correction for sector and country effects, though causal interpretation must be cautious.

This evidence is suggestive, not definitive. Too many other factors play a role, institutional quality, natural resources, demographic trends. It would be intellectually dishonest to make causal claims based simply on correlation patterns.

What we can conclude

Effective leadership is not a constant. The same person may excel in one context and fail in another. For economists this is relevant because we often implicitly assume that management is a neutral factor, a constant that we can ignore. But if leadership style systematically varies with performance, then we are missing an important piece of the puzzle.

TSF is itself a simplification. Just like econometric models it reduces complex human dynamics into measurable categories. The difference is that TSF acknowledges this modesty. Frameworks are tools for understanding, not truths.

In a world where AI exponentially increases the speed of change, adaptive leadership becomes only more urgent. Rather than claiming that TSF is the solution, I suggest we treat leadership like any other important variable: with methodological discipline, healthy scepticism, and openness to disproof.

Perhaps that is the most important lesson from my econometric background: acknowledge your assumptions, quantify your uncertainty, and always stay willing to adjust your models when new data justifies it.

For the interested reader you can read the article series by Michael here.